By Kelechi Deca

Few days ago, the news made rounds across the Nigerian public narrative space which mostly dwells in within the cyberspace of the death of a certain Police officer of the position of a Divisional Police Officer (DPO) causing massive eruptions of ‘thanksgiving’ from most commentators.

The huge expressions of reliefs and testimonials flooding the cyberspace was to say the least shocking, not only because people refused to abide by the scriptural injunction of mourning with those who mourn, but the fact that one person could have such free reigns to commits such atrocities without restraint says a lot about policing in this country. Same issues that led to the #EndSars protests are daily manifesting all around us.

Expectedly, there were some who went about admonishing those ‘celebrating’ the death of the said officer, on the need to “speak no ill of the dead,” which reminds me of the words of our elders that “A man whose relative is shamelessly displaying ugly dancing steps, suddenly feels the urge to scratch his eyebrows”.That is probably why our ancestors admonished that “Anyone who sees where a fowl is scattering feces with its legs should chase it away, because no one knows who would eat those drumsticks”.

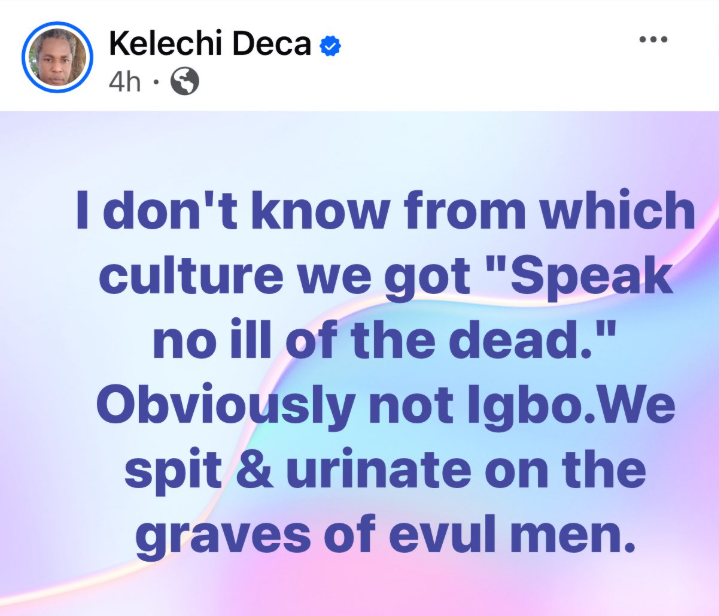

Whenever I read certain things from Igbo people, I wonder where and how they internalized such beliefs. I believe I am old enough, well immersed in Igbo culture, various customs, and traditions, to what was never there.

I also understand the fluidity in certain aspects of Igbo culture when what is generally regarded as sacrilegious, or a taboo are committed without the expectations of the consequences of the act, on the perpetrators simply because the Umunna agreed that such act must be perpetrated.

Let me not get unnecessarily deeper for the undiscerning.

I often get exasperated trying to juggle certain cultural assumptions especially when people generalize issues. The advantage and also challenge of living in a multicultural society is that one has to be circumspect when interacting with others of a different cultural background.

What is acceptable to you might be offensive to another. However, while walking the tight rope of that balancing act, we should equally admit the fact that while using your own cultural values as the standard to police others, it is imperative to try and understand their own perspectives, because they may be responding to from their own cultural backgrounds.

The practice of praising someone who evidently lived a bad life at his funeral is unIgbo. According to the tradition of my forefathers, the first step of paying an evil man back is abstention of the Umunna from participating in his funeral rites.

In those days, the corpse of a bad man was left abandoned for his immediate family, and his Ikwu Nne (Mother’s relatives), because according to our culture, the only people who cannot deny you are your mother’s relatives.

According to the ways of our forefathers, irrespective of the crime a man commits, as soon as he ran and takes shelter at his mother’s people, he gets a temporary reprieve because it is a sacrilege to cause him harm in the village of his mother, for if his blood touches the ground of that village, the wrath of the goddess of the earth would be invoked.

That’s why when a man starts misbehaving, his kinsmen would send emissaries to his Ikwu Nne to warn him, because they’re the ones that would share the consequences of his stupidity when the shit hits the fan.

Interestingly, the culture also leaves a lacuna that would enable the killing of a criminal even in his mother’s village without heavy consequences, if the execution is exceptionally necessary. This is to ensure such protection is not abused by evil men

But on “do not speak ill of the dead”, no. We used to urinate on the graves of evil people.

Men used to conserve their urine and tasking their bladders just to have the opportunity of emptying it at the grave of the evil man.

Women use spits to marinate the fresh red earth. Knowing what would likely befall your family at your demise is a way of keeping men in check.

I was tempted to think the loss of that aspect of our tradition is because of the influence of Christianity across Igboland. But Biblically, there were clear evidence of how the remains of evil people were treated. For example, dogs ate Jezebel’s corpse dogs licked Ahab’s blood. Of the thoroughly detestable Judaean king Ahaziah we are told that he died with no one’s regret. Proverbs 10:7: “The memory of the righteous is blessed, but the name of the wicked will rot.”

As I searched, I stumbled on a piece of information that threw light on the source of the phrase “Speak no ill of the dead.” It seems to have traces back to ancient Greece, specifically to Chilon of Sparta, one of the Seven Sages of Greece around 600 BC. The original Greek phrase was τὸν τεθνηκóτα μὴ κακολογεῖν, meaning “Of the dead man do not speak ill.” Later, the Latin version “De mortuis nil nisi bonum” (meaning “Of the dead, say nothing but well”) became widely used, especially after the 15th-century Latin translation of Diogenes Laërtius’ work. Over time, this sentiment spread across cultures, influencing social norms about respecting the deceased.

That is probably how it came to us via the influence of the Greko-Roman civilization on the western civilization which was force-fed to us through colonialisation. However, I am of the firm belief that we should not discard the ethos of our culture and embrace the hypocritical norm of beatification of men and women whose lives oozed nothing but evil while they lived.

Kelechi Deca, a journalist and public affairs analyst writes from Lagos.